Long before the Big Apple’s famed Greenwich Village coffeehouses came a turn-of-the-century group of bohemians. They sought a utopian way of life sans social, political, or moral constraints.

The Maverick Colony of bohemians, actors, dancers, painters, and “queer” folk were people who broke free from the patterns of society.

They were drawn to places like Jane and Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead’s Byrdcliffe Arts Colony, expressly purposed in 1903 to be an art-making institution. However, Hervey White, one of the men who helped Whitehead find the perfect spot for Byrdcliffe, became disillusioned as the original fostering of freedom and creativity seemed to be a bit over-structured for his taste.

White left Byrdcliffe in 1905 and, along with Fritz van der Loo, purchased a farm in the Hurley Patentee Woods and envisioned it as a new art colony where old restrictions on individual freedoms would be replaced with an environment where men and women could live freely. White called it Maverick, with a simple creed: “Do what you want to (as long as you don’t harm others).” White’s vision was for those who marched to the beat of a different drummer, or perhaps even played a strange hand-made drum for that matter. Visual artists, writers, crafts-folk, musicians, and actors were pulled in the Colony’s direction, as if the grounds were magnetized for creativity.

Allan Updegraff, a novelist and a pioneer Woodstock dweller, interviewed novelist and poet Hervey White for the New York Times on July 30, 1916. This was the first summer of concerts consisting of a simple recital by a Russian singer, an American dancer, and accompaniment by the Metropolitan Orchestra. Excerpts from Updegraff’s article told of White’s investment and goal in buying the farm that would become the Byrdcliffe and Maverick Colony and the doubts that White could succeed at his goal with so little money. “When I invested in this farm, ten years ago,” White said, “I did it with the idea of gathering some good musicians during the summer months and giving chamber music in a rustic music chapel among tall trees at the foot of a hill. The farm cost $2,000 and I happened to have $200 in cash at the time, so turned that over to the owner.”

White explained he became a good financier by approaching a neighbor who owned a sawmill. He told the neighbor he needed lumber, “for the bungalows where the musicians were to live.” His plan was if the neighbor would supply lumber and help build some cabins, “I promised to repay him out of the rent the musicians would pay for the bungalows.” The neighbor agreed. “I then explained to a Woodstock storekeeper that I’d have plenty of money as soon as I got my bungalows built, a dozen musicians in them, and the rent collected from the musicians—who would, incidentally, help swell the storekeeper’s summer trade,” White continued. “The storekeeper at once granted me unlimited credit. Yes, high finance is a great thing!”

The name “Maverick” was derived from White’s 1890 visit to his sister in Colorado when he was told of a local white stallion living in freedom. The locals called it the “Maverick Horse.” In 1911 Hervey wrote a poem, “The Adventures of a Young Maverick,” with the poem’s hero being the Maverick Horse. White felt it was a suitable symbol for everything he cherished—freedom, spirit, and uniqueness. So in the summer of 1924, White commissioned John Flannagan, a sculptor who joined the summer artists at Maverick, to carve “The Maverick Horse.” Flannagan was paid the prevailing wage of fifty-cents per hour. Using only an ax, the massive piece was carved from the trunk of a chestnut tree in a few days.

The 18-foot-high sculpture portrays the horse emerging from the extended hands of a man who seems to be emerging from the earth and marked the entrance of the road leading to the concert hall for 36 years. Protecting it from the elements, painter Emmet Edwards moved it into his studio where it remained for 20 years. The horse was moved in 1979 to the Maverick Concert stage and was mounted on a stone base.

In the years following the first concert, an increase of complex presentations, mostly conceived and written by Maverick residents, became popular—along with skits, plays, and pageants. These included the 1917 production of “Catskills’ Rip van Winkle” complete with nude nymphs and a mockery, scorning the Kaiser in 1918. A memorable 1924 production, “The Ark Royale”, featured an 80-foot pirate ship built on the set and burnt to the ground for a most spectacular climax to the performance.

But in the midst of the artistic productions, there was another event that took place called “The Festival,” founded by White in 1915 at the recommendation of resident musicians as a means of raising money for the digging of a much-needed well. The Festival’s initial success transformed it into an annual event open to the public and became the central fundraising method for projects at the Colony.

The Festival was a bohemian carnival filled with collective spirit held on the Colony grounds during the afternoon and evening of August’s full moon. As darkness prevailed, the event became a theatrical spectacle with riotous performances by locals, followed by a costume ball that lasted until morning. The spectacle was originally held in a stone quarry, but as the Festival attendees grew to greater proportions and outgrew the area, the Maverick Theater was built for the event in 1924.

Festival-goers passionately embraced the annual theme with outrageous costumes and avant-garde behavior. Eventually this type of unconventional conduct attracted more than just locals, and visitors from afar came to get a peak at scantily-dressed women or of a particularly renowned painter in outlandish attire. However, growing popularity also gave way to the presence of unsavory sorts of outsiders—namely gamblers and bootleggers in an age of Prohibition.

The New York Herald Tribune reported over 6,000 in attendance in 1929, and an estimated 2,000 more gate-crashers marred the Festival with reports of difficulty in audience control, drunken brawls, robberies, and even rapes. With the necessary intervention by the State Patrol, by 1930 local censure and protest called the event “sinful and immoral” and White was, eventually, compelled to suspend the Maverick Festival in 1931 following 16 prosperous events. White felt the festivals had fallen victim to strong outside forces and were being led toward a materialistic end.

This was the end of an era of Festival fanaticism. The Colony returned to the more subdued artistic endeavors and musical concerts, which have made Maverick Concerts America’s oldest continuous summer chamber music festival and winner of the Chamber Music America/ASCAP Award for Adventurous Programming.

Maverick Concerts, the Maverick Colony, and the quiet arts colony of Byrdcliffe continue the vision of Hervey White as a summer music venue. They represent a venerable tradition of community respect for the “liberal others” in the populace.

For more information, concert schedules, and history of Maverick go to maverickconcerts.org or call 845-679-8348 or 845-679-8217.

Photo Credits

Photo Credits

1) Panoramic Courtesy of the Woodstock-Byrdcliffe Guild.

2) Taking a Break from the Festivities by Stowall Studios, ~1920.

A group, with many children, is taking a break to have a snack in the tall grass of the Maverick grounds.

3) Actor and Actress Posing by Stowall Studios, Woodstock, ~1924. Scene from Comedy of Errors with two unidentified members of the Percival Vivian Players posing. Open Air Theater. Woodstock Public Library District.

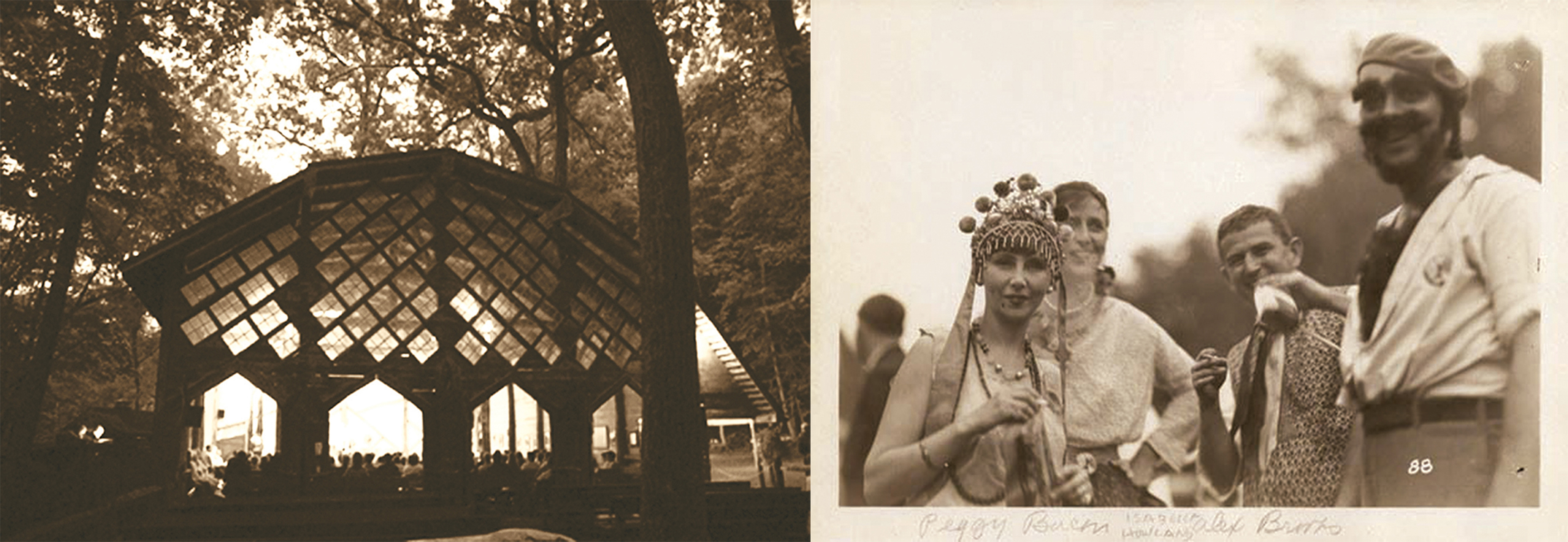

4) 1916 Maverick Concert Hall today by Simon Russell.

5) Peggy Bacon and Friends by Stowall Studios, Woodstock, ~1920. Peggy Bacon (left) a popular author and illustrator of children’s books, poses with Isabella Howland (second from left), Alex Brooks (second from right), and an unidentified man.

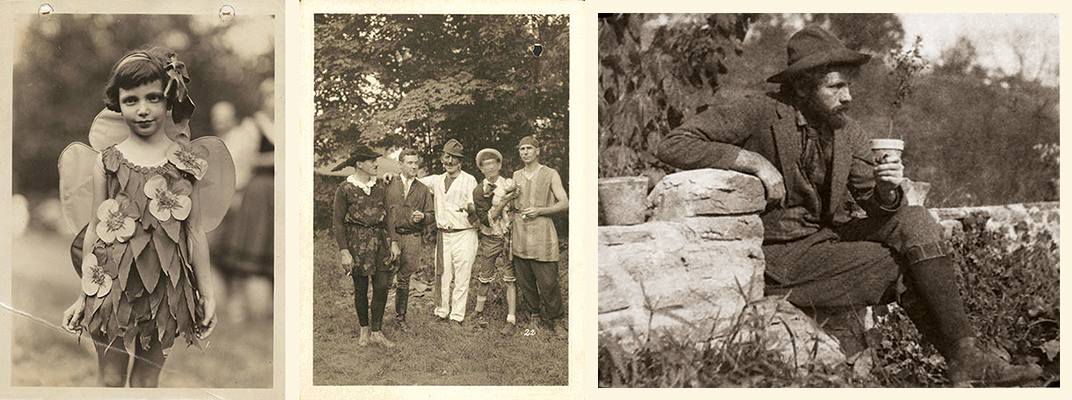

6) Fairie(ly) charming by Stowall Studios, Woodstock, ~1920.

Woodstock Public Library District, www.hrvh.org.

7) Dashing Young Men by Stowall Studios, Woodstock, NY.

1920-1929. This group photograph includes (from right to left) Mr. Reisner, Al Peters, Mr. Temple, Ted Milner, and Wedge Smith, all in costume for the festival. Woodstock Public Library District, www.hrvh.org.

8) Hervey White. This photo was taken in about 1903 by an unidentified photographer. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Go online to newpaltz.edu/museum/exhibitions/maverick and click on menu option “VISIT THE EXHIBITION” for incredible sepia photos of personalities from the early Maverick Festivals and events. Also go to Hudson River Valley Heritage at hrvh.org and put Maverick Festival Collection into the site’s Search to see the Woodstock Public Library’s photography collection.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save