Early this morning, a pair of enormous black vultures landed on a cliff top edge in the Mohonk Preserve just a few feet away from me. Two hundred feet above the wall’s base and fifteen hundred feet above the Wallkill River far below, they sat, swaying in the cool breeze, and began to preen one another in a most intimate and graceful fashion. A shout from far below broke the spell a few minutes later, and, first one, then the other, spread six-foot wings and leaned forward towards the abyss, effortlessly rising into space and gliding away.

I have the remarkably good fortune to spend about a hundred days a year rock climbing in the Shawangunks. It is my passion and my profession. As a climbing guide, I work in a variety of other places around the country each season, but it is here that is home and where I spend far and away the most time. One of the fringe benefits of my job is having a “bird’s eye view” of some of the region’s most spectacular inhabitants.

The Mohonk Preserve and Shawangunks, in general, are teeming with life. There’s a fantastic array of creatures thriving all around us, yet most of this life is hidden from view. Animals are shy; they are nocturnal or use their natural camouflage to stay mostly out of sight. Of course, there are exceptions: deer will sometimes ignore our presence to some degree in favor of a particularly savory browse, small birds will flit back and forth between feeder and forest, and the odd fox will lope across a meadow seemingly oblivious to us (but likely well aware). Raptors, on the other hand, are easy to observe on virtually any day, most any time of day. They are aloft, hundreds of feet above, slowly gliding, unafraid of our presence. These are the ravens, hawks, falcons, and vultures that call the high places along the ridge home.

Red-tailed and red-shouldered hawks are the most common bird of prey along the Shawangunk Ridge.

Red-taileds can be seen perched on tree branches and light poles along the edges of roads and meadows. Red-shouldered hawks keep mainly to wetlands, marshes, and swampy areas. While they both do soar high above at times, they hunt primarily from a silent roost for small animals like mice and voles (and the odd chicken), swooping down to surprise their prey on the ground. Similarly sized—about 20 inches long with wingspans as wide as 50 inches—from below red-shouldered hawks have clearly visible dark stripes across their tail feathers and have red shoulders, while red-tailed hawks have a light-colored breast sometimes speckled with dark spots and, of course, red tail feathers.

Crows and ravens are challenging to tell apart.

Not truly raptors, I am including them here because they are so common in the Gunks and quite beautiful to watch. They are both jet black and similarly shaped. Ravens, though, are much larger than crows. Adult crows measure 17 inches beak to tail with a wingspan of 33 inches, while a raven is over two feet with a wingspan as much 59 inches. Ravens are also more reclusive and less common than crows and also a bit disheveled—raven’s feathers are messy, especially on the chest and neck. From below, the giveaway is that the end of a crow’s tail feathers makes a flat edge while a raven’s curve like a shovel or arrowhead. Overall, both ravens and crows do less soaring than other large birds. Great places to see them, especially the shier raven, are along the Undivided Lot Trail behind the yellow chapel on Clove Road/County Route 6 and between Sky Top Cliff and Duck Pond.

Raptor comes from the Latin root raptare meaning "to seize and carry away"

Peregrine falcons are the world’s fastest living creature.

They feed almost solely on other birds, gliding high above the forest and then diving at speeds in excess of 200mph, snatching their prey from the sky with powerful, sharp talons. I have seen them dive, smash into their prey, knocking it unconscious, and then circle back to catch it as it tumbles spinning toward the ground. In early season courtship, peregrines also perform a breathtaking aerial dance. Despite being driven to near extinction by hunting and the widespread use of pesticides, peregrines have been brought back from the brink in our region by the efforts of the Mohonk Preserve and the Department of Environmental Conservation. Every year, areas of the Mohonk Preserve are closed to rock climbing to allow nesting falcons room to nest and raise chicks successfully. The climbing community has long respected and supported these efforts.

Peregrines are generally easy to find and observe.

They are noisy with a distinctive piercing cry, as well as an unmistakable whistling interspersed with its often-anxious screech. They are relatively small for a bird of prey, measuring 16-20 inches with a 30-40 inch wingspan. From below, look for pointed wings bent slightly back and a long, narrow tail structure with a boxy straight edge. A distinct dark hood and a mustache off the edges of its yellow beak are obvious indicators at perch. Walking along the Undercliff Road below the Trapps area of the Mohonk Preserve is a great place to see peregrines, as is the summit of Millbrook Mountain in Minnewaska State Park.

The bald eagle is also back in full force, and the best time to view these regal creatures is in the fall and winter.

The adult bald eagle’s token white head and tail make them easy to see perched in treetops and on cliffs. And if you’re lucky enough to see one in flight, you can’t miss their six-to-seven foot wingspan. It gets trickier, however, to identify a young bald eagle; their plumage stays brown until about five years of age. Eagles mate for life and tend to use the same nest for their entire lives, which can be as long as twenty-five years. They love to nest in tall white pines and prefer to be near water. Their nests are huge—they can be as deep as eight feet and as wide as six feet and weight hundreds of pounds! If you ever come across obvious destruction of a bald eagle nest, be sure to report it to the DEC’s Wildlife Diversity Unit.

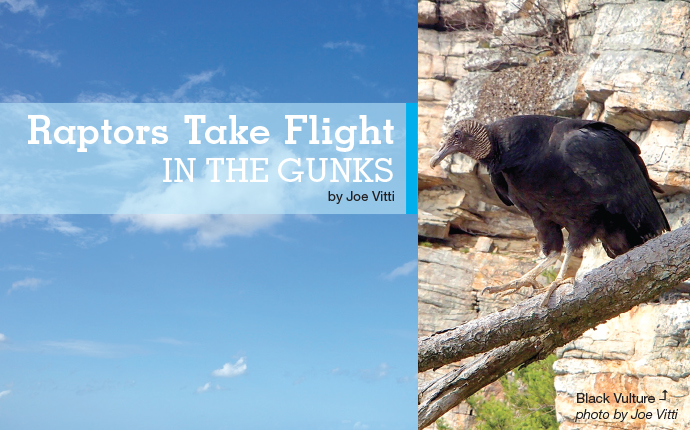

The Shawangunks are the farthest north that black vulture populations have reached so far.

They have been highly successful, nesting along the high cliffs of Minnewaska State Park and the Mohonk Preserve. Their sense of smell is not quite as refined as their larger cousin’s, the turkey vulture, and black vultures spend their days searching for carrion, which the turkey vulture, with its superior olfactory sense, often finds first. The turkey vulture is the most widespread vulture in the United States and is known for its red, featherless head, while the smaller black vulture has a grayish head and a much shorter tail and wingspan.

A little lesser known raptor in our area is the American kestrel, which is actually a small type of falcon.

On average, the kestrel is about 9 inches long and has a 22-inch wingspan. What the American kestrel lacks in size, it makes up for in color—the males’ slate blue wings are simply gorgeous. Unlike other raptors in this area, this little guy’s population is dwindling because of the loss of open grassland habitat, a sure loss for us spectators. Wild populations are being studied for pesticide levels and will hopefully prove to reduce potent toxins so we can all have a healthier earth.

The owl is considered a raptor too, though you are far less likely to see owls because of their nocturnal habits.

Their fluffy look is not to add to their good looks, but rather these special feathers help to make their flight virtually silent—another reason why they elude us humans. Some common owls you may encounter on the ridge if you are lucky include the great-horned owl, barred owl, short-eared owl, and the Eastern screech-owl.

Bird Calls & Warnings:

· Black vulture — whoooooooshhhh

· Turkey vulture — ksssssshhh-uhhhh

· Red-tailed hawk — ksheeeer

· Peregrine falcon — chur, chur, chur

· Bald eagle — ki, ki, ki, ki, ki, ki, kur

· American kestrel — killy, killy, killy

· Barred owl — hu-hoo-huhoo or “Who cooks for you?”

Interesting raptor facts:

· Female raptors are generally larger than males.

· Raptors all kill prey with their feet. They use their curved beaks to tear prey apart.

· A red-tailed hawk can spy a mouse from 100 feet away.

· Owls cannot turn their heads 360 degrees. They can, however, turn their heads 270 degrees, but many other raptors can do this as well.

· All raptors have three eyelids.

· Most raptors prefer monogamy and mate for life.

Joe Vitti is a full-time rock and ice climbing guide with Alpine Endeavors. He lives with his family in High Falls and leads trips here in the Hudson Valley, as well as climbing areas throughout the United States.